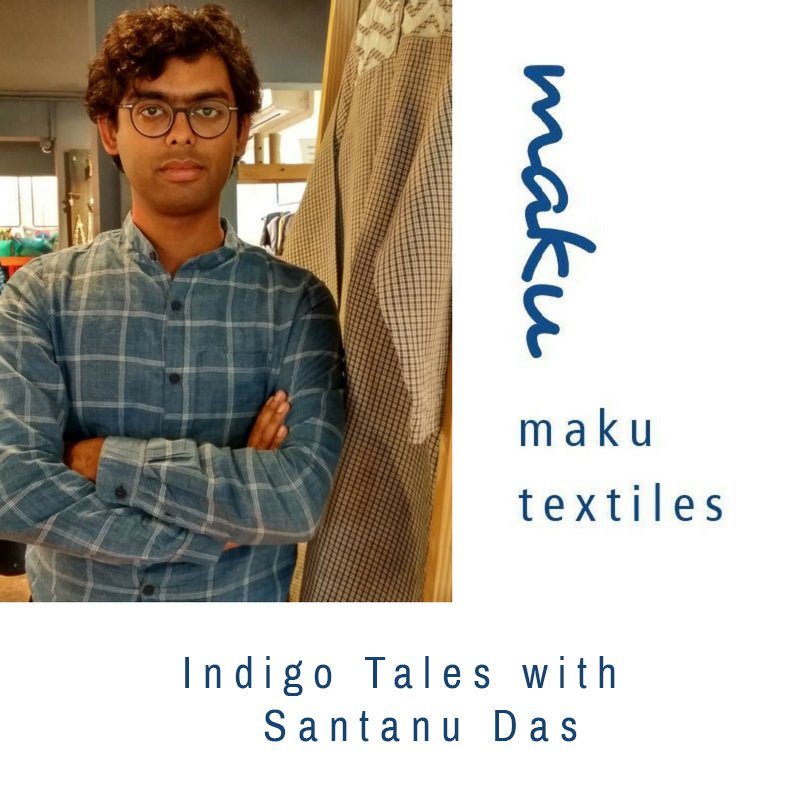

A graduate from National Institute of Design, Ahmedabad, Santanu hails from West Bengal and seems to have found an impeccable way to give back to his motherland. His label’s name Maku means a weaving shuttle in Bengali and is completely synonymous with his idea of working slow fashion movement against rapid industrialisation in the modern scenario.

Having studied and observed various nuances of fashion in India and New York, the designer ultimately found his solace in reviving the forgotten weaving traditions of West Bengal. Here are a few excerpts from the conversation that took place between Santanu Das and Falguni Patel, Ciceroni’s editor and Operations Head at Options Ahmedabad.

Falguni: Why did Maku choose indigo as its signature colour?

Santanu: In the current time and age, people have become quite intolerant to changes around. There is a very fine line between being sensitive and intolerant, you see. We keep striving for more and better options. There is a choice galore, be it picking menu for food through the day or selecting clothes to wear. Human mind is bombarded with decision making in this fast paced world. When one wants to pick a pink or blue shirt, there are umpteen options in colours and textiles. Much of time is wasted in making these decisions. There needs to be a shift in attitude of consuming; mindfulness has to be the primary element. We wanted to narrow down these choices at least in the way people consumed clothes.

It’s about knowing what we want, what we appreciate and siding with that. Hence, we thought of narrowing down our choices with only one colour, natural indigo and made it our brand colour. Invisible Fashion is what we call it; where the form and silhouette is understated. Much akin to taking black and white portraits where the clothes aren’t important but the persona is . We wanted our clothes to be invisible, like second skin to the body.

It is a step to balance the global ecosystem by generating fewer demands in clothes and make consumers wear something which is sustainable and comfortable.

Falguni: Where is the indigo procured from, especially with the mindset of farmers after Blue Revolution?

Santanu: We work with three farmer families in Tamil Nadu who have been producing indigo from generations. We then get them dyed in West Bengal for our range of apparels in different shades. Handwoven garments always take time from crop to final product; we prefer to work with farmers and weavers who are experts in their domain.

Indigo plantation is a rarity in India now and we want government to take a note of this. A plant that was once highly sought after and coveted became a banned product due to British imperialism. Last year Maku was a part of Indigo Sutra, an international symposium organized by Sutra Textiles Ltd in Kolkata to highlight the growing resurgence of indigo in India. There is a need to address the issue of indigo crop production in the country. Both government and farmers need to be convinced of the benefits of the growing popularity and thus demand of indigo, not only in fashion but also in hair dyeing industry.

The Indigo revolt or Nil vidroha was a peasant movement and subsequent uprising of indigo farmers against the indigo planters that arose in Bengal in 1859. Indigo planting in Bengal dated back to 1777. With expansion of British power in the Nawabate of Bengal, indigo planting became commercially profitable because of the demand for blue dye in Europe. The indigo planters persuaded the peasants to plant indigo instead of food crops. They provided loans, called dadon, at a very high interest. Once a farmer took such loans he remained in debt for his whole life before passing it to his successors. The price paid by the planters was meagre, only 2.5% of the market price. The farmers could make no profit growing indigo. The farmers were totally unprotected from the indigo planters, who resorted to mortgages or destruction of their property if they were unwilling to obey them. Even the zamindars sided with the planters. Under this severe oppression, the farmers resorted to revolt. It eventually led to the famed Champaran Satyagrah led by Mahatma Gandhi in 1917 after which the farmers across the country stopped indigo cultivation. Currently only families in Tamil Nadu are involved in indigo production. With more designers opting for natural indigo, the demand is rising for indigo cultivation – a cash rich crop otherwise.

Falguni: Which craft forms do you work with ?

Santanu: We work essentially with Jamdani and Tangail craft technique. Jamdani, a celebrated craft form, was earlier meant for only jamindars. The women in regular income group opted for Tangail sarees in their daily wear. We use both these craft forms in our collections at Maku Textiles. We use khadi, cotton and fine silks in our textile repertoire.

Falguni: How is the acceptance of slow fashion in India?

Santanu: Consumerism is heavily seeped in mindsets of people. What we are attempting is at changing mindsets on consumption. A Maku woman is the one who knows what she wants and she swears by it. She isn’t the one who gets swayed by choices. We are dealing with behavioural shift currently. We want to initiate an alternate dialogue to sustenance. Maku garments will last for 5-7 years if taken care of properly. The more you wear it, the more you wash, it gets finer and finer. We have foreign clients who wear Maku apparels as their daily wear, that’s how much they find our apparels comfortable. In India, we find that there is a small percentage of women who are comfortable with our ideology.

While Shantanu and Maku are changing the way people buy, it would be great to witness how Amdavadis are responding to slow fashion movement. Buying 10 new clothes per month, obviously from sustainable label, will still add to that landfills and environmental issues. Will you be a conscious consumer and be a part of slow fashion movement?